What matters in this discussion – in any discussion over a technology really – is who’s designing it, who controls it, and who stands to benefit?

Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

This piece started off as one that would delineate the difference between the terms “DWeb” (as in decentralized Web) and “Web3” (as in Web 3.0). It seemed like a useful exercise to tease out the communities that implicitly or explicitly support these terms. But the more I dug into it, the more I realized this wasn’t that interesting in itself.

The disagreement over these labels, and what is even included in the purview of each, felt like a distraction from what’s actually being negotiated as people define and claim allegiance to DWeb or Web3. What matters in this discussion – in any discussion over a technology really – is who’s designing it, who controls it, and who stands to benefit?

Decoding DWeb vs. Web3

Even if definitions aren’t worth harping on, looking at who uses DWeb versus Web3 and what they seem to signify for people is a good starting point for that inquiry. So for the sake of setting basic context, it’s worth parsing the jargon a little.

Let’s start with what the terms have in common: they both point to a present shift in networked technologies wherein some level of distributed ownership, control, or management is core to their operation. Those who associate with these movements champion user self-determination over the data and the rules that govern their platforms. By virtue of espousing “decentralization” as a core value, most projects that span the DWeb and Web3 ecosystems concern themselves with questions of shared ownership and governance.

I’m fairly confident that how I’ve described these terms so far wouldn’t be that contentious, but where it gets spicy is when you start to project ethical attributes to these movements. Despite their similarities, it’s undeniable that the terms now carry different meanings and serve distinct purposes; so much so, that people are explicit about supporting or steering clear of projects associated with one or both of these words.

Web3: An Impending Web

Though it was popularized by Gavin Wood, co-founder of Ethereum and Polkadot, the term Web3 was already used to describe a future semantic Web – where all linked data is machine-readable, shareable, and reusable across the Web. Under the World Wide Web Consortium’s definition of a “semantic Web,” which was then synonymous with “Web 3.0,” there were several types of web standards that existed that would enable this kind of “Web of data” including Extensible Markup Language (XML) and Web Ontology Language (OWL).

Nowadays though, Web3 has come to signal something more specific: protocols and platforms that involve blockchain and distributed ledger technologies, including cryptocurrencies. Based on an overview of some mainstream definitions, it has largely become a buzzy marketing term meant to signal that a project is part of a new phase in the evolution of the Web (even Twitter founder Jack Dorsey thinks it’s a buzzword). The word itself points to its temporality – it’s the next thing after “Web 2.0” – and is a sign of being part of an inevitable progression of the World Wide Web.

Reflecting on the term Web3, Evgeny Morozov points out that while its proponents evoke it as a revolutionary new phase of the web, they rarely (if ever) address fundamental issues of power that made the old web toxic. He writes that many Web3 advocates are adversarial towards “Web 2.0” projects for their monopolistic control over user data. Yet despite Web3 products’ core offering of enabling end-users to own their digital assets, most don’t engage with the underlying political economy that fundamentally shapes the priorities and incentives of these tools. For one, Evgeny notes that many of the same VC investors who are salivating over the profitability of Web3 ventures are the same characters who were behind funding and shaping the most disastrous, centralized “Web 2.0” companies.

Taking a less critical stance, CEO of Bluesky, Jay Graber gives an elegant overview of the Web’s phases of history – describing Web 1.0, Web 2.0, and Web3 as “the hosted web, the posted web, and the signed web,” respectively. This breakdown is helpful to contextualize the current wave of cryptographically timestamped global ledgers, aka blockchains, within a technological history of the Web. Jay’s definition of Web3 is notably more expansive than what you normally hear, harkening back to its original definition of a semantic Web. She therefore includes not just blockchains, but any protocol that is “self-certifying”, including older protocols like Git, PGP, BitTorrent, as well as newer ones, such as IPFS, Hypercore, and Secure Scuttlebutt (SSB).

Jay isn’t saying that it’s exclusively new tech that holds the potential to unlock user sovereignty over data and identity, but that we can look to older protocols as well. While hers is a provocative and tidy definition, I’d be hard pressed to say that anyone else would encompass these other non-blockchain protocols under the umbrella of Web3. What is telling though, is that it’s a purely technical definition, without any mention of the organizational or economic issues that plagued “Web 2.0.”

As Evgeny would point out, what’s the narrative that this is playing into? Are the problems that plague the Web purely technical? If sufficiently decentralized, will these technologies fix all that ails us? There’s a major oversight when one focuses solely on the technical affordances that were available at each stage of the Web, and points to them as their fatal flaws. It strongly implies that all we need to do for this new Web to work in the long run is to just code our way to the right systems. Instead, the true issue at hand is: How do we architect those systems to reflect the complexities of diverse human interaction and need in distributed, digitally-mediated contexts?

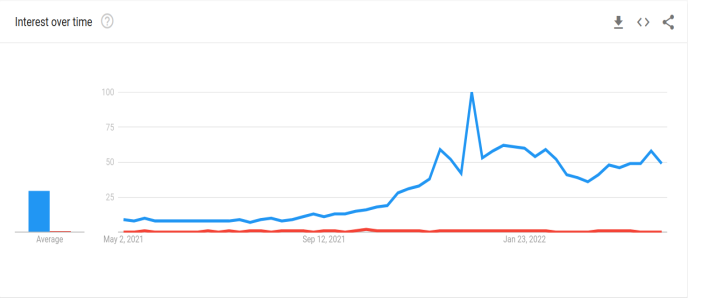

This is a screenshot of a Google Trends search of the terms comparing Web3 (blue) and DWeb (red) made on 28 April 2022.

DWeb: An Evolving Web

While the term “DWeb” is still one of the usual suspects commonly used in this space, it’s not used nearly as heavily as a marketing buzzword. For many, it’s become more of a general adjective than a word describing a movement or a major shift in the evolution of the Web.

One of the loudest advocates of this term is the Internet Archive, which has been hosting events and discussions on the Decentralized Web since 2016. Under the purview of its DWeb organizing work, the Internet Archive has included any kind of technological project that is decentralized across the technical stack – from community networks, federated social media platforms, peer-to-peer protocols, to even older, tried-and-tested protocols such as email and torrent files. Since 2020, they have doubled down on the values-driven core of its work through the DWeb Principles.

I should disclose that I have been a core member of the Internet Archive’s DWeb Projects team for the last three years. As part of this work, through a collaborative process with several dozen stakeholders, I co-stewarded the process to define the five overarching principles: Technology for Human Agency, Distributed Benefits, Mutual Respect, Humanity, and Ecological Awareness. Our aim was to put a stake in the ground and affirm the values of those building alternative network infrastructure. Instead of merely being not centralized, we wanted to define what it was that we stood for.

Though some have pointed out that it sounds too much like dweeb, I find “DWeb” to be an incredibly useful umbrella to organize under. It seems to attract people who are not only interested in building a new Web (and many Webs) for the sake of profit, but also for the sake of addressing concrete challenges, especially those faced by the most marginalized communities. And while people do cite the ways the Web used to be more decentralized, the term is temporally ambiguous. It doesn’t have the baggage of seeming like a new phase, nor is it under threat of having an expiration date. This creates room for the movement to evolve as we gain more allies and build a network of solidarity. By calling it a DWeb, it reminds us to continue wrestling with the question of what it is we’re decentralizing.

Decentralization as Praxis

Too many self-defined Web3 projects – at least those that involve tokenomics – have been harmful. They’re either scams, burn a grotesque amount of energy (particularly those based on Proof-of-Work), or require tons of hardware usage (leading to immense waste).

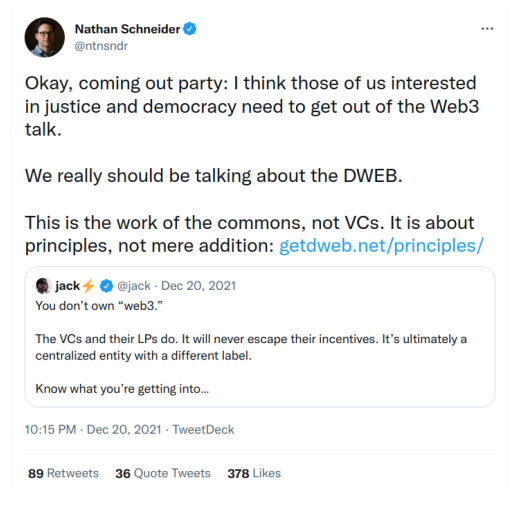

Even still, several solidarity-minded people have written about the potential of cryptographic protocols to design new institutions when the current ones are failing us. Emmi Bevensee wrote a thoughtful, nuanced piece about the glimmer of hope that blockchain projects bring to redesigning social systems. Nathan Schneider explicitly says, “Crypto is a tool for designing institutions” and has been advocating for ways for crypto projects to embed good policy into their code. And Alice Yuan Zhang urges us to seriously engage with the failures of these tools and ask who and what we are decentralizing:

Decentralization as praxis is rooted in direct action, striving to abolish capitalistic economics and supply chains which encode mass oppression into large-scale systems with many actors and minimal accountability.

Crypto-based protocols contain the potential for large-scale coordination that is unprecedented, including the ability to collectively monetize and compensate people for their labor. Which is all the more reason why we can’t let such powerful tools for mass coordination become monopolized by those who merely want to amass wealth or control.

We need to contend with the fact that it’s just not feasible to expect ourselves to effectively tackle systemic challenges based on goodwill and volunteerism. Values-first, free and open source, and peer-to-peer projects struggle financially. They often don’t compensate their contributors enough, if at all. Too many of them fizzle as they try to raise money through grants or crowdfunding efforts, while competing against similar projects that are injected with venture capital and whose sole fiduciary purpose is to make a profit for its shareholders.

So if I were to oversimplify the ideologies of DWeb and Web3 as “justice-oriented” and “profit-oriented,” respectively, I would say that these movements have an incredible amount to learn from each other.

Though Web3 is aligned with venture-capital, there’s a staggering amount of thinking and experimentation happening around governance in this space. This is an outcome of decentralization being a core facet to these projects.* Whatever their motivation, blockchain projects have unleashed people’s imagination about what’s possible when people own and control things together. When money is explicitly part of the equation, they’re able to think more pragmatically about how to direct those resources and make things happen.

One project that’s able to straddle both worlds is Open Collective, a software company that provides financial tools for groups and communities to manage their finances transparently and consentfully. (Hypha is a fiscal host on the platform.) Open Collective has remained purpose-driven, even as they’ve taken venture-capital to grow their project. Now, they’re exploring how to “exit to community” – to shift from a privately-owned company to one owned by its community of stakeholders. Despite the fact that their tooling isn’t reliant on a blockchain to coordinate funds between people, Open Collective is arguably one of the most successful platforms for decentralization that exist. That’s because they’ve remained committed to focusing their energy on decentralizing the thing that matters most: power.

Building new and shinier tools out of the same political and economic conditions will do nothing to fundamentally change the world. But “decentralization” is also not a value in itself, and it’s not enough to build the kinds of technological networks we need to confront intensifying global crises. People need to continue to discuss, shape, and re-shape collective values. With those values held at their core, communities with common interests can collectively coordinate and embody them, first and foremost through how they govern themselves and treat one another. After all, the current internet is a reflection of shared values; the question is how we embed justice and mutual care into the Webs to come. Instead of expecting some technology to save us, we need to organize and save ourselves.

*It’s likely many cryptocurrency projects maintain the semblance of shared ownership through token-based governance as a means to stay “sufficiently decentralized” – which allows them to stay out of the clutches of regulatory institutions like the US Securities and Exchange Commission.