Reverence for the Spaces In-Between

An Interview with Sultana Zana

Influencers, Instagram, the proliferation of state propaganda—today’s political economy runs on attention. “Value” is abstracted; speculation determines worth. The incalculable messiness of the world is flattened by predictable capitalist logic. But for Sultana Zana, the tools of the market also hold the possibility of subverting the market. As the digital world births new hydras of monopoly, the global finance machine can become a spore itself: seeding authentic entanglements, cultivating an economy of slowness, and redirecting our attention to wilderness everywhere.

Based in Bangalore, Zana is a performer, painter, sound artist, researcher, media artist, physicist, former nano-technologist, mycelial-enthusiast, insect-fanatic, and network-inoculator. Their home is a lab where everything is inoculated with everything else—and they take the same approach to the rest of their work. In “Heaven 2.0” , an intelligent assistant teaches a time traveling soil expert about a future cyber-based world, invoking the metaphor of a mycelial network to meditate on the critical threats to our common future. “Landscapes” scales up the elegant complexity of our belowgrounds, compiling field recordings from various patches of the Earth in order to transport us to a perceptual world 300 times smaller than our own. (“Unpredictable chaos is beautiful by its very nature because it fails systemic opression,” they write. “This unpredicatble chaos might kill me, but its beauty is not lost to me.”)

The polymath’s current project, “Fieldness” , is their most notable experiment yet: an open-source blockchain and ecological database converting experiences with non-human beings into crypto-assets. “Tap into wilderness that is everywhere,” Zana urges, “even though the capitalistic monoculture has really killed the vibe.”

Zana’s practice is playful, but they’re no utopian. The world is “contaminated,” and so are we; a crypto-conspiracy to celebrate life and propagate joy is inherently tainted too. How might we build architectures of symbiosis, porousness, and connection within a sterile world? What can a practice of deep listening and careful observation offer in the face of mass extinction and climate collapse? Their probings bring to mind Robin D. G. Kelley’s line : “no one’s hands are completely clean.”

Stemming from our commitment to collaborative and decentralized forms of knowledge-making, we conducted this interview a little differently. We invited all of our Issue 02 contributors to join the conversation and meet one another. So we, the contributors and editors of this issue, sat down with Zana over Zoom, logging on from Toronto to Berlin to Bangalore. We (Mai, Udit, Ben, Tal, Margaret, Eeshita, Liaizon, and Kola) talked about redefining value, the dynamism of paranodal space, and learning to see and appreciate what has been made invisible.

—COMPOST

Mai: Where do you come from, both in terms of life experiences and creative shaping?

Sultana: I technically trained as an instrumentation and control engineer, and then I did a Master’s in Experimental Media at Srishti in Bangalore. Technical training doesn’t really say what cultures we are from in this time. I have a friend who is trained in exactly the same things as me, but he makes these really technical designs for the defense of the country. But I could say that I come from cultures of cybernetics, cognitive science, mycology, ecology, natural sciences, soil sciences, network theory, media art, media studies, cellular means, and the crypto-world. These are the spaces which are my sources, which I have learned from, and continue to learn from.

Mai: Can you describe your current practice?

Sultana: We live in a world of social and physical architectures which enforce boundaries and behaviors, and which train us to ignore a lot of things. My practice is to see what is not visible: to create work that can momentarily break the social forms and constructs that we are bound by; to reveal what is not actually seen in what has always been there before us.

Our social behaviour—sitting in a certain way, talking in a certain way—are traditional, cultural; these habits and learnings influence certain boundaries on us. And our cognitive plasticity eats all of this learning, imprinting these things in our mind.

In my work I attempt to shift this, or break this. This is possible only momentarily, but that is enough. A moment can transform one. That leaves something with the viewer, in experiencing whatever form of work that I make.

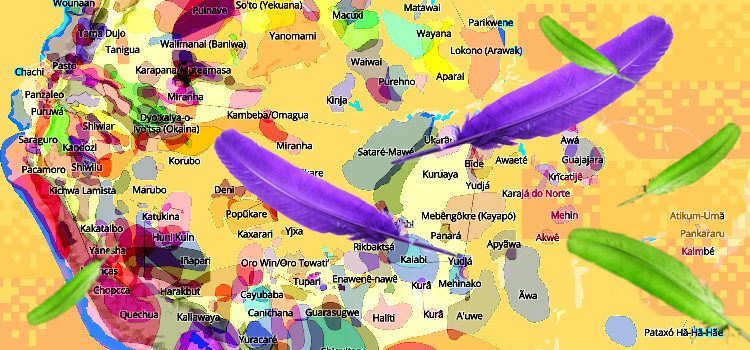

Screenshot of the fieldness frontend via Sultana Zana

Mai: To come to this sort of practice by way of an engineering background, you must have reached a certain level of disillusionment. What was your Matrix moment ?

Sultana: A long time ago, when I was 19 or 20, I was doing my engineering and not feeling satisfied. Not feeling satisfied is fine, but everywhere I went I encountered this kind of hierarchical structure. I was going to the lab, working in computation technology, trying to write papers, and I was so outside of everything: the building, the architecture, the structure, my professor. I didn’t know what was wrong, but I just knew that this was not right.

Additionally, the heteronormativity and enforcement of “male” and “female” was too intense.

In government universities in India, there are huge sprawling areas that are mostly wild. This wilderness is carved out to create all these architectures of power: you enter and there’s this straight road, which leads to this big building, which is where the director sits, and when the director arrives everyone stands. In that scientific space, there are (very few) people doing very cutting edge research, and then everyone else filling the gaps. I was not interested in filling the gaps, and I was not fitting in. I just couldn’t get it.

Ben: This room is full of disillusioned engineers?

Kola (in chat): Yes most definitely lol.

Ben: There are three disillusioned engineers in here!

Sultana: I can only say about how things are in India, and about being a queer person here. I still wasn’t out as gay at the time—I didn’t know people who were, in my college or wherever—and it is only in recent times did I begin to identify as non-binary. At that time, I didn’t have these words. That was the time that opened some things for me. Also quantum physics really helped. I was also doing research work, and nano-technology, trying to find spaces which really interested me. I was consuming all of these different things, and I knew I was finding some sources somewhere, but I was not able to find my way in the structures. I realized: it’s not going to happen. I would have liked to be in academics in sciences but it was not possible to be myself in that space.

Udit: Your work is very rooted in geography, and in space. How specific are the social and physical constructs you name—the enforcement of boundaries that make us see or ignore different things—to place: to your home in Bangalore, to India?

Sultana: The space that I’m occupying right now is not very different from the kind of spaces that you are occupying, but of course there will be differences. In my experience of being in the West, what is understood to be okay and not okay between people is quite different. Here, because we’re so densely populated, or maybe it is just cultural, it is a lot more porous. At the same time—if we look at caste, at the segregation of neighborhoods and villages and towns, between Hindus and Muslims—it is not. But that’s not my day-to-day; everybody’s day-to-day is their own sort of microcosm. This porosity is not geographically bound. In the West, there’s a lot more distance between people. It will be a lot of time before I can ask you a personal question. But these bubbles we live in are not bound by geography alone anymore.

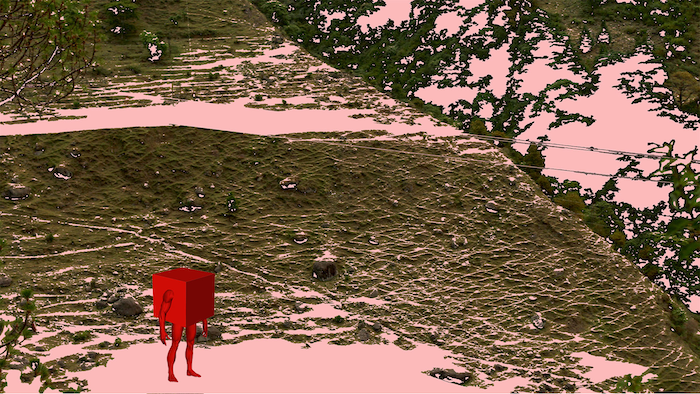

A banner image for Fieldness via Sultana Zana

Tal: As we’ve been thinking up inoculation together, we’ve been talking about your project “Fieldness” , which so beautifully expands this issue’s conversations about value, networks, crypto-schemes for connection. Can you unpack the project for us?

Sultana: “Fieldness” comes from two different ideas I was sitting on. One of them is the question of what is value and what is valuable. It doesn’t make sense. To cut down a one thousand year old Amazon rainforest to plant palm oil trees? Even with the cost benefit analysis, which is a capitalist way of seeing, it doesn’t make sense. One can see this, and yet we continue to strive for things which actually are not that valuable.

The other thing that I was looking at is this idea of paranodality. There’s a book called Off the network by Ulises Ali Mejias that explains this idea, and which really speaks to what I mean when I say my practice is looking at what is hidden.

If I say “network,” you’ll imagine dots and edges, the standard diagram, or what we might call “nodal space.” This is what we see when we see a network, but we never think of what that black space underneath the dots and edges is. What is that space which does not make it to the network? Paranodal space, which is that dark space, is actually full of activity. It’s never dead space, it is what is not visible. It is the parameters of what makes it to the network, and it is interesting to look at that parameter. What is it that did not make it to the network?

Whenever we open a map, for Uber or whatever, we see roads, malls, shops, restaurants, coffee shops, other kinds of places to buy things, maybe a park or two. We see the map and it makes us believe that we are seeing almost everything, but that can almost never be true. What we don’t see, what doesn’t make it to the map, is what I’m interested in.

Even in the middle of Delhi—the most dense city, which has been occupied for hundreds of years—I can still find places which are quiet, where there are birds and trees, where it’s actually wild. There’s a book called Trees of Delhi by Pradip Krishen who has written about all the trees in this city. They exist everywhere; everywhere this non-human life flourishes. Fieldness is meant for these margins. It is a queerness of sorts, because there are always margins of all kinds. That is what Fieldness is.

A picture of a walk inside Delhi’s Sanjay Van via Sultana Zana

There was a question in the emails we exchanged earlier about what it would look like if Fieldness were to manifest fully. It would reach all the ecosexuals, all the cyclists, all the people who go to these places—behind the garbage dump, where you can see the most beautiful sunset, or notice insects which you’ve never seen before, which embody a niche (every specie embodies a sensorial niche) and evolution of billions of years.

Sultana: On the one hand, Fieldness is just a platform. It’s like Instagram, in some kind of way. But it also begs the question, what am I doing? And it is then that you can ask the question, what is value? What is valuable? And to then ask that question by connecting it to a kind of crypto space is fun! It flips it. It’s conceptual; I can dream. You cannot really ask the question of what is value without touching the financial systems that we are living in.

Udit: You do this via blockchain, which many have been critical of both for amplifying the sort of financialization and speculation we’re confronted with and also for its environmental effects, and then as an artist your practice is pushing back against current capitalist framings, including this technology. Can you expand on the choice of tools you use and why you decide to work with certain technologies?

Sultana: There’s always a sort of a critical backlash to any sort of system which is taking hold, but that does not stop it from happening, because the people who are actually living and breathing this sort of framework—pumping it and making it flourish—are not the ones reading the papers, resizing the ecological costs. I mean, Elon Musk is talking about energy! He’s blowing a whole bunch of money on these huge steel rockets, and he’s talking about energy.

That’s a contradictory and complicated space. How do I knock on the doors of the people who are actually running the system? If I have to talk to Musk about something, I have to make a small rocket and bump his large steel one. I’m living in some small, tiny, very dense neighborhood in Bangalore, and I’m going to shoot a rocket from here. We live in the world and it’s dirty, it’s filthy, so we have to put our hands in the filth. And that’s what I enjoy doing. That’s the only way to really live, I suppose.

Tal: The filth you’re talking about—the “architectures of power” you mentioned earlier—is human-made filth. In its emphasis on details, on what is not visible, paranodality turns our attention toward the non-human. I’m curious what potential Fieldness holds for reimagining, even undoing, the capitalist human.

Mai: Another way of thinking about this, to be sort of on the nose with the theme of this issue, is to consider the idea of positive virality, the hope of inoculating systems of capital, or notions of progress. This issue explores fungal growth—approaches to life that eat away at those very concrete, strict, rigid, inflexible systems that are themselves eating the world, digesting life and the complexities of life into what you refer to as “value.” What is it about your practice that inoculates the hierarchies you have talked about, to blur certain boundaries and elevate those marginal experiences?

Sultana: I have a collaborator who I run this collective called NOTAAT (Not One Thing at a Time) with. We have this small little world, these small little echo chambers. I make Fieldness and it stays in a sort of closed room, so how do we even make a dent as media artists? As people who are looking at what is happening, who are looking at what other people are not looking at, looking at all the bullshit being shown on televisions and news in India?

Our situation is so bad right now with this government, these power structures we’re up against. We’re the largest population in the world and there’s a huge amount of noise being created which is drowning out everything that is relevant. How do you make a population blind? Just by creating noise. From India to Afghanistan to India, we’re going through information warfare.

Kola: Extremely true. Weaponized content worldwide…the attention economy is so overpowering right now.

A picture of a fallen tree via Sultana Zana

Sultana: At the same time, if I wanted to show someone how mycelium grows fifty years ago, for example, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. The tools we have makes it possible to position a human being and a microorganism at the same scale. It’s possible to blow things up, to blow things up quite literally, to project things on a large building. These are tools that can bring us to a sort of scale above the noise, above our threshold for noise.

But there’s always a negotiation. For example, open source software is a complicated space. How does open source flourish in the kind of way it has? It’s not just the goodwill of individuals. Corporations can also not function without it; they are writing into the open source, and taking from that.

How does an idea grow? How does a spore spread? Wind. And we have two types of wind right now: financial-winds and attention-winds. I feel that is my struggle as an artist—how to negotiate that, to make a dent—but it is a messy space. It is super messy, and it is never going to be fully clean. The contamination has to understand that even the contamination can be contaminated.

Udit: We often think about the term “making a dent” in reference to artist practices that are more interventionist than sustained; something is created and it is a momentary statement, and then we move on. How do you as an artist move beyond an intervention to scale it up, so that it shifts towards something like a movement? This idea that Mai was talking about earlier, about positive virality—how do you make this more than you, more than the sort of echo chambers you were talking about earlier?

Sultana: Networks. I mean, there is no other way. We live in a really close world in some ways. India is a country of 1.8 billion people but I do believe that ten people can make a difference. It has been done and it is possible. Network is a large word; it contains so much underneath it. A network which has any power has something which is making them live—a sort of food, a sort of mind sauce, a source that is active in all the nodes of the network at the same time, believing the same ideas, coordinating. In the case of mycelial networks, for example, there are many dead networks, but then something comes alive, and then that alive network dies, and then something else comes alive.

Mai: You’ve talked about mycelial networks in various ways already, but could you talk about your fascination with fungal networks and entanglements directly? How has your play with fungal life influenced your work, and your practice?

Sultana: What fascinates me about mycelium is that it is an organism which chooses to be a network. That is to say, mycelium is a network, but it’s also an organism. When we speak of networks, we speak of all mathematical, topological forms, sort of a concept with nodes and edges. But there is also the sensorium of the network—meaning something which is not static, something which is growing, which moves by growing, in which the only way to move somewhere or to touch something is to grow to that point, to leave my body behind.

It helps to think of this because we are kind of emerging like networks. Our neural networks create our consciousness; a sort of a form which creates something on top of itself which is larger than the sum of its parts. Mycelium is an interesting being, and also a metaphor to understand networks in a way that is different from how we would see it as a mathematical form.

When I think of digital networks, there’s a distance between me and it, and it is not a living being. When I think of a living being, it is almost as if it’s me. It is interesting to think about this idea of the ego when we’re talking about positive virality. We’re left/right beings, we’re linear; we can give our lines of awareness one thing at a time. Seeing one word at a time, saying one word at a time, holding one concept in our mind one at a time. One can change the size and weight of the spot, but our attention is really like a spot.

But for something which is not a centralized network like we are, which is mycelium, I wonder how it is? How time is? Where is the attention? They are sensing all the time, of course, just like we are. If someone is walking on soil, there is a sense of where the light is, because I—the mycelium—have so many fruiting bodies all over. I know where the sun is, because I always grow in the shadow side. I know where the moisture is, I know where the elephant comes to pee or to eat me. So I have an awareness as a being, but where does awareness lie at any point of time? Where is the center of it?

Wakest: “I have so many fruiting bodies,” wow! The idea of our thoughts and activity online being our fruiting body is beautiful. There is never such a thing as a static network. It is always messy and chaotic and alive. Permanent entropy and growth.

A photo of a moth in camouflage via Sultana Zana Another photo of a moth in camouflage via Sultana Zana

Sultana: We are unable to think of a sort of decentralized thing; we haven’t and I don’t think it’s possible. But it’s nice to try to dissipate the center, to question where the attention is. For mycelium, there’s a sense of time, a sense of night and day, of when the moon comes, of when monsoon summer comes—because it’s all related to how mushrooms sprout. Mycelium might not know the earth is round, but that’s irrelevant here. It’s irrelevant to me, also; it doesn’t give me anything. What does it mean to have multiple points of attention at the same time? How does a network make decisions? How do we transfer intelligences amongst each other? That’s what fascinates me.

Mai: There’s this big question about time in what you’re saying. While the world is obsessed with newness and progress, mycelial networks are, on the other hand, constantly decomposing and regenerating. For them, time is nonlinear. It makes me think about a paragraph from your article, TIEM , in which you write:

This flat surface with unchanging permanence creates an illusion that things need to be pushed forward with time. Since nohting ever changes or evlves on its own - the capitalistic idea of ‘revamping’ or ‘renewing’ florishes - because we like change. Our mind likes new things. So there is the dual pressure - that we must catch up and we must push everything in to the future. Everything must be ‘renewed’ before the future arrives.

You alluded to this a bit in your answer just now, but can you elaborate on your thinking about temporality—in particular how we slow down, or even just begin to relate to time in a different way?

Sultana: We are in the middle of this huge shift. We’re changing who we are. One hundred years ago, one individual would function in certain social patterns and species, and we evolved for that sort of local social structure. Now we’re moving into both a global web structure as well as an individualistic one. And in this process we are terraforming the planet, we’re losing our species, we’re going through mass extinction. I don’t think I can answer your question, but I can say what my observations are, about why it seems impossible to slow down, or to not become obsolete.

Udit: It seems like the centrality of a node is related to the perception of time.

Sultana: We need to be active to keep being in the nodal space of the world. The sort of feeling like, “Oh, it’s been a while, I should put an Instagram story today, otherwise people will forget me.” I’ll just drop into the darkness of the binodal space, where the networks we’re in we are not considered to be in. We created the web, and now we’re creating lots of worlds on top of the web—and, on a planet of 7 billion people, about a billion people are working to do that every single day. Every bit of food I have eaten with my own money has been given to me because I created something which went on the web.

There’s a project about this that I am still writing proposals for, hoping to be able to do. There’s something called Electronic City in Bangalore. It’s the place where all the tech companies and coders and developers work. All places around Electronic City are posh—they have pubs and clubs, things happening late at night, it’s on fire—and then there’s the rest of Bangalore—which is kind of slow, another kind of space. And now there is money flowing into both; these engineers and coders consuming so much food and water and electricity. I can use the metaphor of an organism again to just say they are taking a lot.

My question is about the roots which are pumping all of this. Everything from the vegetable markets to the farms, which bring the food that feeds all of the cleaners and workers and staff here. All of the water that pumps into these places. All of the electricity. Where is all this stuff coming from? And where is all of it going? I don’t know yet, but it feels like time is really related to how we are, to which networks we belong to. We’re in the middle of a flux; that’s the question I’m leading with right now.

Mai: Wow, thank you.

Eeshita: Loved listening to you Sultana!

Margaret: You’re doing really interesting, thought provoking work. Thank you.

Udit: This was all really great. Sultana, a lot of people in our networks are thinking about things you’re thinking about in very similar ways. If you’re ever in Toronto, I’d love to invite you to come by; we’d have a lot of things to talk about.

Sultana: Let’s write this address down. I’ll send a rocket.

We built this little tool for you to inoculate other web spaces with the ideas and stories contained in this issue. To re-publish this piece under the terms of the license, click below to copy the markdown.